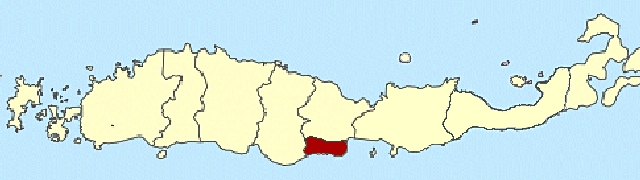

Nage KeoNage and Keo (pronounced 'nagay' and 'kay-o') are two adjacent areas, nearly identical in many details of culture, language and societal structure, that were joined into a single jurisdiction by the Dutch colonial authorities, a forced unity perpetuated by the Indonesian government which eventually led to nearly complete amalgamation. During Dutch colonial rule, the territory of the raja of Bo'a Wae (Boawae) stretched from coast to coast, including a variety of different peoples including the Islamic community of Mbay in the north and the southern community of Tonggo peopled by Endenese settlers who intermarried with Keo. In the Islamic coastal areas the supplementary-weft technique predominates - which falls outside our sphere of interest. Though we follow common practice by using the combined nomer Nage Keo, when we are discussing ikat textiles in fact we are only dealing with the Nage, a term that nowadays covers a larger group of people than it would have in pre-colonial times. What connects the various groups so named, is that they all have tree totems rather than animal totems like most tribes in the archipelago,

The Nage and Keo speak a simple language, of the same family as Malay, but not as evolved. (See the section on Ngadha language). Like many other remote living peoples such as several South American Indian tribes, they believe that individuals do not own the land, but that, conversely, the land owns them, in the same sense as a mother can be said to own her children. This philosophy is reflected in a number of traditional expressions. 'Mother Land, Father Stone' (Ine Tanah Ame Watu) is the title for a Lord of the Land, and 'Mother Plain, Father Field' (Ine Ku'ame Lema) is how the lower ranking Overseers of the Land are referred to. This sense of being children of the land leads Keo people to regard land registration certificates issued by the government as spurious, not binding in any way. Anyone, including migrants, can gain access to ancestral land by observing various rituals and social obligations - and will lose access if they contravene the adat. The Indonesian Government nowadays recognizes the traditional links between ancestors, land and mythology and issues documents indicating that the land of certain regions claimed by particular clans belong to a named ancestor or embu, and hence to the embu's descendants, the children of the land, the anak tanah. The Nage and Keo have long been known for their unique form of institutionalized pre-marital and extra-marital sex. Assuming the practice effectively ended in the 1990s by conversion to Christianity, it is probably best described in the past tense. The relationship involved young unmarried women openly becoming temporarily attached to men - either married or unmarried - for the purposes of sex. The custom came just short of institutionalized promiscuity: a man could not have more than one temporary mistress. Such relationships (which sometimes served as precursor to marriage) were not just socially accepted, but positively valued and encouraged - an arrangement that led former president Sukarno to write about it in a manner that suggested enthusiasm for the practice. The lover presented to the parents items similar to those that would be transferred in the case of marriage, though of less value. In return, the man might expect a feast at the end of the contracted relationship, and sometimes a textile. Predictably, in the case where the girl was of much lower status or a slave, arrangements became less formal and generous, probably slipping into the open sexual licence that excites the imagination not just of presidents but of ordinary men the world over. Some girls might have only two or three 'lovers', but the more attractive might have as many as dozens, and some men spent their entire wealth on short term liaisons. Primitive indeed is the word, as it is hard to see how the Nage and Keo system is substantially different from an organized renting out of daughters.  A Nage Keo ikat sarong, a hobo pojo of the type singi to in the National Gallery of Australia. Nage Keo ikat textilesIkat weaving in the Nage region, as elsewhere, was surrounded by numerous taboos. Weaving for instance could not be done while the men were away hunting or waging warfare. Traditionally, three types of textiles for women were produced: the plain hoba do'i, the hoba niki nado decorated with plain coloured stripes, sometimes alternated with narrow band of ikat dyed with indigo, and the hoba pojo with much broader bands of ikat in indigo and usually also a similarly decorated central field, alternated with bands in morinda red. This most visually attractive type has by now become the characteristic Nage attire for women - and practically the only one seen in museums. The central field motifs are limited to rows of dots,wavy lines and simple rectangles - and tumpal endings. The weaving is invariably very loose. As Hamilton remarks: "Even the best old cloths in museum collections coarsely woven." Ours is no exception. Nowadays only hobo pojo are still produced, albeit in small numbers and not always using natural dyes.In the past Nage men also wore ikat cloths, called sada géa when used as hip wraps, or sada bhago when worn as a shoulder cloth. These were woven with richer patterning and more precise weaving than sarongs, but loose hipwraps went out of fashion early in the 20th C. when changing notions of modesty (presumably introduced by missionaries in hopes of introducing chastity) moved the men to prefer tubular sarongs of the kind made in the Mbay coastal regions, decorated not with ikat but with supplementary weft. A sad loss in our view, as supplementary weft, however beautiful, cannot compare to ikat in terms of technical complexity. Very few sada are left for us to admire. As Hamilton notes: "A number of these cloths survive in museum collections." Our two old sada belong to the very few in private hands.  Wife and daughters of Raja Oga Ngole of of Bo'a Wae. The young woman in the middle is the only one who wears an ikat sarong, a hoba pojo. Note the intense look in the eyes of the woman on the right, likely the effect of sirih (betel) chewing to excess, a diagnosis reinforced by what appear to be swollen cheeks. The habit still affects many in Nusa Tenggara. Photographer unknown, early 20th C. Tropenmuseum of the Royal Tropical Institute (KIT), Creative Commons Licence.

Wife and daughters of Raja Oga Ngole of of Bo'a Wae. The young woman in the middle is the only one who wears an ikat sarong, a hoba pojo. Note the intense look in the eyes of the woman on the right, likely the effect of sirih (betel) chewing to excess, a diagnosis reinforced by what appear to be swollen cheeks. The habit still affects many in Nusa Tenggara. Photographer unknown, early 20th C. Tropenmuseum of the Royal Tropical Institute (KIT), Creative Commons Licence.

| ||||||